We tend to picture ancient Egypt through the lens of gold masks, grand tombs, and pharaohs. But scattered between those glimmering symbols of power are quieter traces — of young girls grinding grain, weaving linen, or fetching water in the shadow of the Nile. And while those traces are faint, they’re there.

Girls Lived, Worked, and Learned — Even If History Didn’t Record It Clearly

Let’s be honest: ancient Egypt wasn’t exactly obsessed with documenting the lives of its everyday children — especially not girls. Most of what survives skews toward the elite. That means boy-kings and scribes-in-training are easier to track than girls sweeping temple courtyards or learning to bake barley bread.

But that doesn’t mean they weren’t there.

In fact, what we do know reveals just enough to raise big questions — and force us to reimagine a past that’s often been overly focused on men.

The Language Problem: What Even Counts as a “Girl”?

Here’s where it gets messy. Ancient Egyptians didn’t document age the way we do. No birth certificates. No school records. Instead, children were often labeled with vague hieroglyphs for “youth” or “child.” And those were tied more to social roles than biological age.

Some records refer to “daughters,” but not always with clarity. In other cases, girls were called “female children,” but it’s never as straightforward as we’d like.

Which means for researchers, the act of identifying girls in historical records feels like chasing shadows.

Still, a few terms pop up, usually paired with family titles — daughter of a priest, child of a servant, niece of a weaver. These crumbs, while small, help shape the bigger picture.

Girls Didn’t Just Grow Up — They Grew Into Work

So what did ordinary girls do in ancient Egypt? They worked — often from a young age.

A girl in a worker’s village like Deir el-Medina might have helped her mother with household chores. If her family had a weaving workshop, she could be threading looms by age eight or nine. Tasks were gendered, but not strictly. Economic need often overrode custom.

Some were likely apprenticed. And while formal apprenticeships were more commonly documented for boys, there’s growing evidence that young girls could also be trained in specific crafts — pottery, textile production, maybe even midwifery.

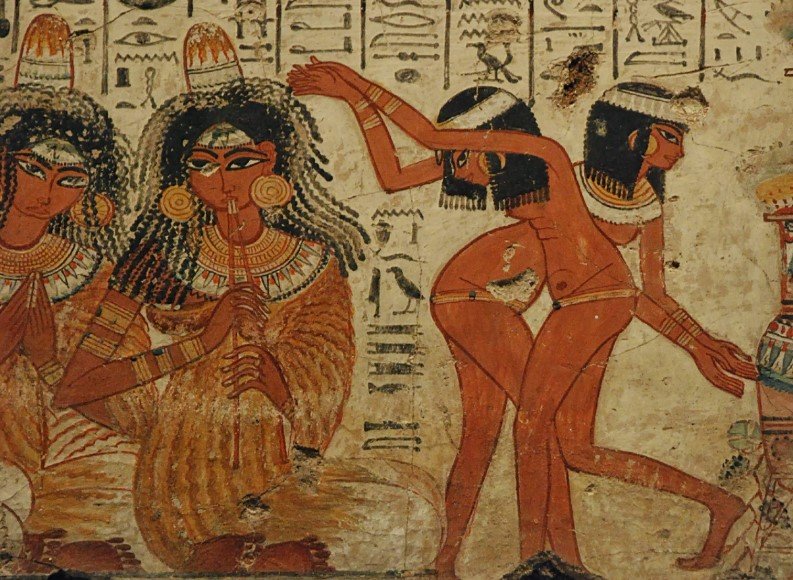

• Tomb scenes show young girls grinding grain, fetching water, and helping older women weave linen for temple rituals or elite burials.

One tablet found near Thebes even depicts a group of women and girls — possibly a family — working together on a communal textile project. It doesn’t shout status, but it whispers something powerful: ordinary lives mattered.

The Numbers Are Scarce, But They’re Starting to Add Up

We don’t have census data or detailed school rolls, but there are just enough archaeological clues to make some educated guesses.

In burial sites across Middle Egypt, researchers have uncovered modest tombs of adolescent girls buried with work tools — weaving implements, grinding stones, and bead-making kits.

Here’s a simplified table based on findings from three key Middle Kingdom sites:

| Site Location | Age Estimate | Associated Artifacts | Suggested Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abydos outskirts | ~10–13 yrs | Spindle whorls, oil jars | Textile work (apprentice) |

| Deir Rifeh | ~8–11 yrs | Clay dolls, grindstone | Domestic labor |

| Asyut tombs | ~12–14 yrs | Loom weights, beads | Craft production |

Again, none of this is conclusive — but that’s the nature of this work. Piecing together splinters, not full stories.

Education Wasn’t Off the Table, Just Uneven

Here’s where things start to shift depending on class. Elite girls — daughters of scribes, priests, or nobility — had better odds of learning to read and write. They might’ve been tutored at home or learned alongside brothers. Their literacy wasn’t just a nice perk — it was social capital.

For poorer girls? Education was more like osmosis. You learned by watching. You absorbed skills by doing. You followed your mother or aunt, not a scribe.

Still, some exceptions break through. A few ostraca (inscribed potsherds) found in workmen’s villages show female names in handwriting that suggests practice — not dictation. That hints, just maybe, at girls sneaking in education, even unofficially.

So What’s the Takeaway? They Weren’t Passive

It’s easy to look back at ancient Egypt and assume women — and girls especially — were passive actors in a man’s world. But that’s far too simplistic.

Girls worked. Girls trained. Girls played roles in temples and households and trade. Maybe not as priests or officials — those roles were rare — but as participants, nonetheless.

More than anything, their stories tell us this: even in a society that didn’t go out of its way to record them, girls shaped their world. And bit by bit, we’re finally starting to see it.