A new study from Israel has shed light on a quiet but devastating trick used by melanoma, explaining how the deadliest skin cancer manages to shut down the body’s natural immune response and keep growing unchecked.

The findings, announced this week, could reshape how future cancer therapies are designed.

A discovery rooted in Israeli and global collaboration

The research was led by scientists affiliated with Tel Aviv University, working alongside international partners in a multi-year effort to understand why immune cells often fail against melanoma.

Their work was published in Cell, one of the world’s most influential peer-reviewed journals, signaling the study’s weight within the scientific community.

At the center of the discovery are microscopic structures called extracellular vesicles, or EVs. These are tiny, bubble-like packets released by melanoma cells into their surroundings.

And they’re not harmless.

Researchers found that these vesicles actively interfere with immune cells, essentially switching them off before they can do their job.

Melanoma’s deadly reputation, explained in numbers

Melanoma doesn’t account for the majority of skin cancer cases, but it causes the most deaths.

According to the World Health Organization, roughly 325,000 new melanoma cases are diagnosed globally each year. About 57,000 people die annually from the disease.

Those figures have puzzled scientists for years. Treatments exist. The immune system is powerful. So why does melanoma still win so often?

This study offers part of the answer.

Instead of hiding from immune cells, melanoma appears to confront them directly, using EVs as chemical weapons that blunt immune attacks before they even begin.

It’s less a shield and more a sabotage.

Tiny vesicles with a massive impact

Extracellular vesicles are naturally used by cells to communicate. Healthy cells release them all the time.

Melanoma hijacks that system.

The study showed that melanoma-derived EVs carry molecular signals that confuse and weaken immune cells, especially those meant to identify and destroy tumors.

Once exposed to these vesicles, immune cells lose their ability to respond effectively. Some become sluggish. Others stop attacking cancer cells altogether.

One researcher involved in the project described it as “immune paralysis,” a phrase that has since echoed through medical coverage of the findings.

And the scary part? This happens quietly, long before tumors become visible or symptomatic.

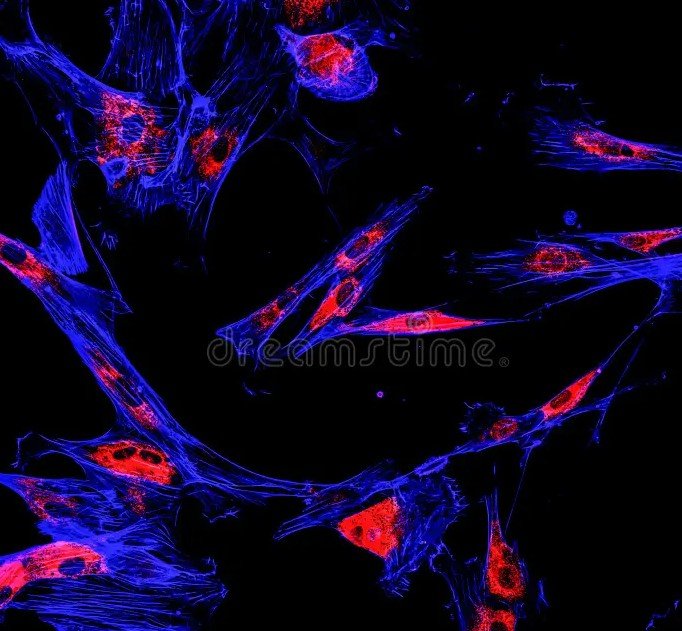

A visual glimpse inside the tumor battlefield

The team used advanced 3D immunofluorescent imaging to observe melanoma cells interacting with their environment.

In these images, melanoma cells glow in magenta, immune components appear in contrasting colors, and cell nuclei show up in blue. The visuals make something abstract suddenly real.

You can actually see how crowded and active the tumor environment is.

What surprised researchers was not just the presence of EVs, but how efficiently they spread. These vesicles travel fast, reaching immune cells well beyond the original tumor site.

That may help explain how melanoma metastasizes so aggressively.

Why current treatments don’t always work

Immunotherapy has transformed cancer care over the past decade. Drugs that “release the brakes” on immune cells have saved lives.

But they don’t work for everyone.

This study helps explain why. If melanoma EVs are already disabling immune cells upstream, boosting the immune response later may come too late.

In simple terms, the cancer gets a head start.

Researchers believe that blocking or neutralizing these vesicles could make existing treatments far more effective. That idea is already gaining traction in oncology circles.

What this could mean for future therapies

The findings open several new research paths.

Scientists are now exploring ways to:

-

Prevent melanoma cells from producing EVs

-

Block EVs from reaching immune cells

-

Reverse the immune paralysis caused by EV exposure

Each of these approaches could be combined with current immunotherapies, potentially improving outcomes without reinventing treatment from scratch.

One researcher involved said the goal isn’t to replace immunotherapy, but to “clear the noise” so the immune system can hear the right signals again.

That shift in thinking could be huge.

A broader impact beyond skin cancer

While the study focused on melanoma, its implications stretch further.

Many cancers release extracellular vesicles. If similar immune-disabling behavior is found elsewhere, this research could ripple across oncology as a whole.

Experts caution that translating lab discoveries into clinical treatments takes time. Years, often.

Still, the excitement is real. Cancer researchers around the world are already citing the study, calling it one of the most illuminating looks yet at how tumors manipulate immunity.

Why this matters beyond the lab

For patients, melanoma can feel unpredictable and unfair. It often strikes younger people. It spreads fast. It resists treatment.

Understanding how it operates gives doctors and patients something powerful: clarity.

This research doesn’t promise an instant cure. But it pulls back the curtain on a long-standing mystery, showing exactly how melanoma outsmarts the body’s defenses.