A quiet revival is unfolding in Cairo, where some of the world’s most iconic antiquities are being carefully coaxed back to life, one delicate brushstroke at a time.

Inside the sunlit conservation lab of the long-awaited Grand Egyptian Museum, archaeologists aren’t just restoring gold and wood. They’re reawakening history — and fulfilling childhood dreams.

A Boyhood Obsession Turned Lifelong Mission

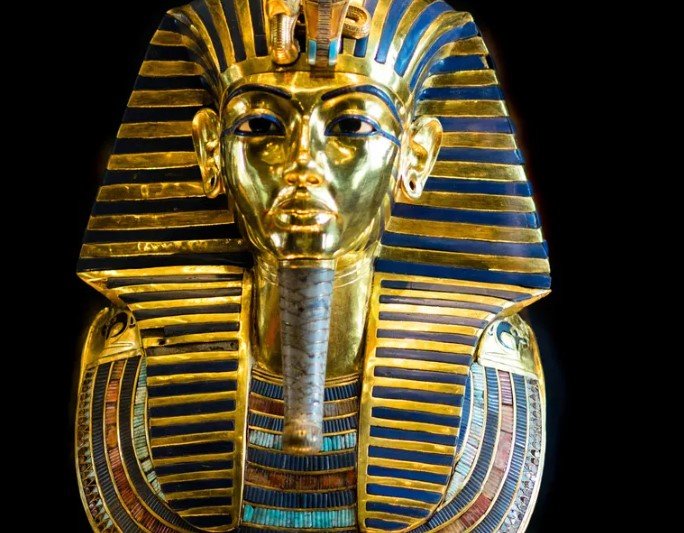

Eid Mertah still remembers the first time he saw a picture of Tutankhamun’s funerary mask.

He was just a kid in a Nile Delta village, flipping through his school’s dusty old history books, tracing the golden contours of the pharaoh’s face with his finger.

“I thought to myself — one day, I want to touch this,” he said.

Fast forward a couple of decades, and that same boy — now a 36-year-old conservator — is leading restoration work on the very treasures that once filled his imagination.

For him and many others, this isn’t just a job. It’s deeply personal.

Tutankhamun Still Casts a Spell

King Tutankhamun, who died over 3,300 years ago at around 19, remains one of the most famous names in Egyptology. Ironically, it’s not because of what he did in life, but what was left behind in death — his tomb, discovered in 1922 almost entirely intact.

The treasures found inside, from a golden coffin to chariots and thrones, stunned the world and redefined how people viewed ancient Egypt. And now, many of those relics are being seen with fresh eyes once more.

Inside the lab, dozens of conservators work meticulously on hundreds of artifacts, some of which haven’t been touched since British archaeologist Howard Carter opened the tomb over a century ago.

Some are restoring massive gilded shrines that once encased Tut’s sarcophagus. Others are fixing fractures in ceremonial furniture or stabilizing golden sandals shaped like lotus flowers.

“We’re dealing with objects that carry soul, memory, and global fascination,” said one senior conservator. “So we move slow — very slow.”

A Home Fit for a Pharaoh

The Grand Egyptian Museum, located near the pyramids of Giza, has been in the making for nearly two decades.

And when it opens in full — a date Egyptian officials still haven’t officially locked in — it will house the entire Tutankhamun collection together for the first time ever.

That’s over 5,000 items. All pulled from the boy king’s tomb.

Here’s what sets this project apart:

-

Each item is being treated by Egyptian hands, many of whom were trained specifically to handle Tut’s artifacts.

-

The restorations are being done in one central lab, allowing for synchronized conservation.

-

For the first time, many of these items will be displayed in their full restored form.

“This is not just an exhibition,” said museum director Atef Moftah. “It’s a reintroduction of Tutankhamun to the world.”

Scratches, Dust, and Ghosts of Colonial Hands

Tutankhamun’s treasures, while dazzling, have scars.

Many show signs of hasty unpacking during the early 20th century. Some pieces were even misassembled by Carter’s team. Others were damaged by time, temperature changes, or earlier restoration attempts using unsuitable materials.

“It’s like finding an old photo album where the pages are crumbling,” said conservation specialist Heba Mostafa.

She’s been working on a ceremonial bed that was warped and flaking. Some damage came from termites, others from the original excavation.

In one corner of the lab, a team was carefully removing resin drips and glue marks — the legacy of earlier, rushed repairs.

For modern conservators, the mission is clear: fix what needs fixing, but never rewrite the artifact’s story.

Ancient Craft, Modern Science

What’s remarkable about the current restoration effort is its blend of ancient wisdom and 21st-century technology.

The museum’s labs are equipped with advanced imaging machines, laser scanners, and 3D modeling software. These tools allow conservators to examine tiny cracks or reconstruct missing parts digitally before making a single physical move.

Below is a simple breakdown of some items and treatments underway:

| Artifact | Condition | Treatment Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Gilded Shrines | Surface dust, cracking | Manual cleaning, stabilization |

| Golden Mask Display Frame | Broken mounting support | Reinforced with resin support |

| Ceremonial Sandals | Dry and brittle leather | Humidification, reshaping |

| Painted Chest | Flaking pigments | Fixative application |

| Bed with Cow Carvings | Insect damage | Consolidation and gap fill |

“We rely on microscopes and CT scans, but also on our fingers,” said Mertah. “Sometimes, your skin tells you what no machine can.”

Restoring More Than Objects

This massive conservation push is doing more than saving relics. It’s training a generation of Egyptian archaeologists who now see themselves as stewards — not just researchers.

“You see a sparkle in their eyes,” said Mona Hassan, who supervises intern conservators. “They’re touching something sacred. And they know it.”

There’s a quiet but growing pride that Tutankhamun — once studied through British museum glass — is finally being restored, preserved, and displayed by Egyptians on their own soil.

At least one conservator described it like returning a son’s memory back to his family.

Whispers of What Comes Next

Outside the museum walls, Egyptian tourism has been slowly climbing back after years of pandemic setbacks and regional instability.

Officials hope Tutankhamun’s full collection will become the crown jewel of a broader cultural revival.

And while no grand opening date has been announced yet, museum staff say the collection is “nearly ready.”

Just a few more artifacts to polish. A few more repairs to finish. Then Tut will be ready to dazzle again.

One technician wiped the dust from a golden mirror and held it up to the light.